L.A.'s preposterous power prices

Other utilities take advantage of cheap solar power to cut customer bills and help the environment. Why won't LADWP follow suit?

By Matthew Tupper and Scott Woolley

When the winter sun shines on Los Angeles County and solar power courses through its electric grid, millions of Angelenos in cities from Santa Monica to Pomona can save money by using that cheap, green energy to charge their Teslas or heat their pools. As the sun sets, those discounted rates, offered to customers of Southern California Edison, disappear and the utility hikes power prices a whopping 127%.

But within the city of L.A., the 3.9 million residents served by its own municipal utility have no similar opportunities to benefit both the planet and their pocketbooks. It’s a mystifying omission for a city that has committed to some of the country’s most ambitious environmental goals. L.A.’s Department of Water and Power offers customers no discounts for using low-cost, low-carbon power when the sun shines. Nor does it charge a premium for dirty, expensive power generated at night by fossil fuel plants.

“We are missing out on a major opportunity for ratepayers to reduce their costs, support the grid, and help the environment,” said Timothy O’Connor, head of the city’s Office of Public Accountability.

In theory, no American city should be better positioned than Los Angeles to prove it can power itself with energy that is both environmentally and budget-friendly. In L.A., unlike every other big city in the country, the citizens own the electric utility, from the plants that produce the power to the poles and wires that deliver it. That gives L.A. a unique ability to modernize its power system without having to negotiate with the private shareholders and state regulators who control America’s other urban utilities.

Yet rather than enabling flexibility and innovation, municipal ownership of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power has kept its grid stuck in the past, charging power prices that make neither environmental nor economic sense — and making a mockery of the city’s public commitment to lead the way into a zero-carbon future.

The LADWP can trace its unusual ownership structure — and the roots of its current policy paralysis — to the Chinatown era in the early 20th century. After scandals exposed plutocrats’ efforts to control the public’s access to water, city of L.A. voters decided to control their own destiny, building an aqueduct, seizing power generation from private hands, and setting up a city-run utility to keep both water and electricity cheap and local. In the rest of the U.S., big cities put their trust in regulators to oversee privately owned utilities.

While both approaches to running a natural monopoly have their drawbacks, for most of the 20th century L.A.’s municipal ownership model did an admirable job of living up to its progressive-era ideals. Angelenos paid lower prices than other Californians served by the big investor-owned utilities regulated by the state. The political checks and balances proved largely effective in keeping the utility aligned with its customers. L.A.’s City Council appoints a five-member board to oversee the utility and employs an independent ratepayer advocate to act as an additional watchdog. Ultimate control rests with the council and city voters, who, if necessary, can overrule both the DWP board and the bureaucracy.

In the 21st century, however, that political system began to calcify. Nowhere is that inflexibility as apparent as the way LADWP has — alone among the state’s big utilities — refused to adapt its prices as new technologies revolutionized the electric system.

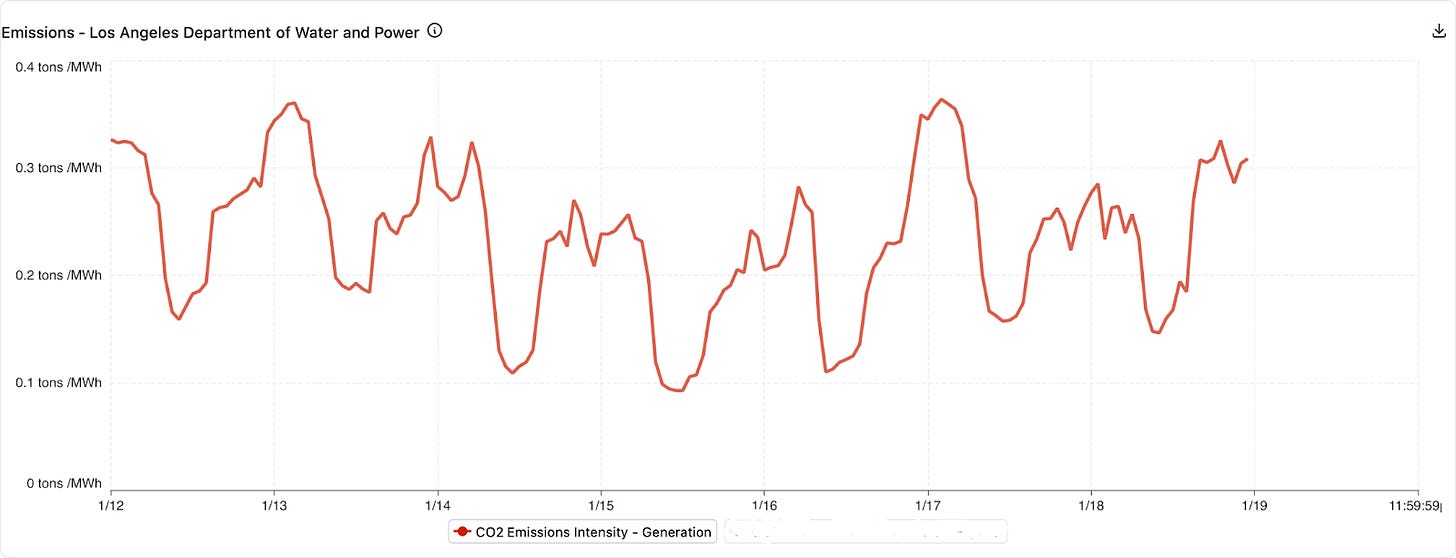

From 2009 to 2019, the price of solar power in sun-soaked California plunged over 90%, according to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. As a result, during daylight hours the grid often can be powered mostly by solar energy. But that also means the amount of pollution required to generate L.A.’s electricity varies wildly depending both the season and the time of day. On winter nights such as last Friday, when the DWP produces most of its power in natural gas plants, generating the electricity needed to charge a typical electric car results in roughly five pounds of carbon going into the atmosphere. That’s triple the amount that would have been emitted during the middle of that same day, when solar power flooded the grid. (See chart.)

Those disparities grow even wider during the rest of the year. Come spring, there will often be more solar power than Southern California can use for several hours in the middle of the day, meaning gigawatts of zero-carbon power go to waste for lack of demand.

In the rest of California, the number of customers who pay prices that reflect the needs of the modern electric grid has been growing for more than a decade. The California Public Utilities Commission, which regulates California’s other big utilities, recognized the obvious economic and environmental merits of “time of use” pricing in 2015, passing a rule to encourage varying prices that benefit both the environment and customers’ pocketbooks. Yet over 99% of LADWP’s residential customers still pay the same flat rate, technically known as R-1A, which sets the same price at noon and at 7 p.m., even though the grid is awash with solar at midday and shifts to power from natural gas plants in the evening. The utility offers a time-of-use rate, but it’s upside down, based on the outdated “peak usage” model, when electricity was more expensive when the sun shines and cheaper overnight. Only about 12,000 of its customers take that option.

Electricity prices are tricky to compare between utilities. (Different utilities vary prices based on, among other things, customer location, time of year, the ratio of fixed to variable charges, and total usage.) A typical LADWP bill charges 24 cents for the first 700 kilowatt hours per month, then 30 cents for every additional kilowatt hour. Southern California Edison customers on its time-of-use rates pay 22 cents for all power used during sunny “super off-peak” hours. Prices jump to 50 cents at 5 p.m.

If LADWP were to combine its overall cost advantage with a modern rate structure, it could beat SCE’s cheap power rates during sunny hours, offering a huge incentive for customers to use clean electricity.

Robert Cudd, a researcher at UCLA’s California Center for Sustainable Communities, cautions that modern time-of-use rates don’t offer an instant fix, since electricity users are “famously slow” to change their behavior. Still, he adds, if L.A. is serious about making its electric system greener and cheaper, the sooner it starts the process of pushing consumer demand to daytime use, the better.

The city’s previous ratepayer advocate also encouraged the city to modernize power prices, telling the city council that “This matter is urgent because power customers need notice of a change before this summer. It can be accomplished with a single sentence amendment to the power rate ordinance.”

That was four summers ago.

LADWP management is eager to modernize rates, but can’t act until the city council allows it. “We support and need modern time-of-use rates,” says Ellen Cheng, a spokesperson.

O’Connor, the new ratepayer advocate, says that while it’s true that the council could amend the law to modernize pricing, complicated state laws mean that the move could have “cascading effects,” including a major reduction in the amount of money the city could extract from the DWP to fund its budget. Last year the department sent $219 million to the city.

But while there are bureaucratic and accounting hurdles in the way of modernizing LADWP prices, there are no fundamental economic or environmental compromises that need to be made. In fact, the opposite is true. “There are savings on the table when you do comprehensive rate reform. Savings for the city and savings for residents,” O’Connor said. “There is a win-win solution.”

And that’s the sad irony of America’s largest municipally owned utility. The politicians who run it are happy to set grand environmental goals but unwilling to take one of the most obvious, painless steps to make them a reality.

Until that changes, it’s hard to take Los Angeles’ commitment to running a zero-carbon electric grid by 2035 as anything more than empty talk.

This breakdown of how municipal ownership became the very thing blocking progress is kinda mind-blowing. The citys ratepayer advocate literally said they need a one-sentence amendment four years ago, yet here we are still burning expensive fossil fuels at night while solar gets wasted during the day. Dealing with utilites in my area made me realize how much bureaucratic inertia trumps common sense, even when everyone agrees theres a win-win solution sitting right there.

With the increase in post pandemic work from home, the time to switch to greater daytime energy use has never been more of a lay up. What a lost opportunity. Great article, LA Reported.